As

we have set out extensively before, the health of a dune/beach system has

little to do with the amount of sand either in the sea or on the land.

So one does not need to spend decades of laborious monitoring of the sand

budget in order to qualify the health of a given beach. (In fact sand mass

monitoring does not say anything about beach health at all). But some knowledge

of a beach's history could serve to advantage, much like a physician takes

clues from a patient's history.

As

we have set out extensively before, the health of a dune/beach system has

little to do with the amount of sand either in the sea or on the land.

So one does not need to spend decades of laborious monitoring of the sand

budget in order to qualify the health of a given beach. (In fact sand mass

monitoring does not say anything about beach health at all). But some knowledge

of a beach's history could serve to advantage, much like a physician takes

clues from a patient's history.

Just like patients, no beach is alike. They are physically different,

and are affected in different ways by the same causes. So a bit of detective

work is needed before embarking on a course of action or before drawing

a final conclusion. But in the main, almost anyone can now assess the health

of one's own stretch of beach.

Not

surprisingly, the main threats to our beaches arise from human activity.

The drawing shows the most important ones, which we will summarise here

from right to left:

Not

surprisingly, the main threats to our beaches arise from human activity.

The drawing shows the most important ones, which we will summarise here

from right to left: When

asked, people do like their beaches. They are just not aware that their

daily actions destroy the very things they like. Many of our actions do

not only destroy beaches but also to a larger extent, our terrestrial and

marine environments. Obviously, our societies will need to make major environmentally

friendly adjustments. All over the world, environmental groups are championing

this cause. It will take time and public education.

When

asked, people do like their beaches. They are just not aware that their

daily actions destroy the very things they like. Many of our actions do

not only destroy beaches but also to a larger extent, our terrestrial and

marine environments. Obviously, our societies will need to make major environmentally

friendly adjustments. All over the world, environmental groups are championing

this cause. It will take time and public education.

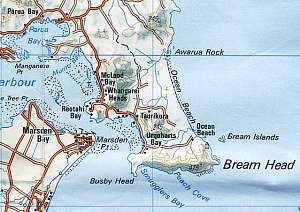

In

the northern part of the North Island, New Zealand, I have earmarked a

number of beaches that are worth saving first. The accompanying map shows

where they are. Each beach is worth saving for a different reason. It is

of course impossible to be complete but everyone knows a beach in his/her

locality that is worth saving first. From the Otama Beach example and the

examples below, a number of reasons and conditions become evident. By focussing

effort on those beaches that are still in a salvageable or even healthy

state, quick progress can be made, while the result is also likely to remain

successful.

In

the northern part of the North Island, New Zealand, I have earmarked a

number of beaches that are worth saving first. The accompanying map shows

where they are. Each beach is worth saving for a different reason. It is

of course impossible to be complete but everyone knows a beach in his/her

locality that is worth saving first. From the Otama Beach example and the

examples below, a number of reasons and conditions become evident. By focussing

effort on those beaches that are still in a salvageable or even healthy

state, quick progress can be made, while the result is also likely to remain

successful.