|

by Dr Floor Anthoni www.seafriends.org.nz/indepth/invasion.htm |

|

|

|

by Dr Floor Anthoni www.seafriends.org.nz/indepth/invasion.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

.

It was amazing to observe how quickly the parchment tubes invaded so many places. In the first few years, the tubes were found nestled in between and under rocks but by 1998 they had seeded themselves so profusely that large areas of seabed became covered, particularly the coastal sheltered sandy bottoms in clear water and the deeper sea bed.

They were easily identified as belonging to the genus Chaetopterus which has always had a member represented in New Zealand.

One would think that identifying a species is relatively simple but

this is not so. There are very few people in the world specialising in

the study of this kind of worm; people who know all the species of this

group of animals and have all the specimens with which to make comparisons.

So a number of carefully prepared worms (prepared by staff of the Auckland

Museum) have found their way to the other side of the world, waiting to

be studied.

We

would like to know whether this is the same animal that has always been

here or if it is a new, invading species. If this is so, it gives one more

reason for protecting our seas from illegal aliens, arriving here inside

the ballast tanks of ships or otherwise. It also raises the important question

of why some animals suddenly increase their numbers so explosively, like

the crown-of-thorns starfish in the Australian Barrier Reef. Have conditions

in our seas changed? Has its natural predator disappeared? If so, who was

it? Will our local fishes learn how to eat it? Will the plague disappear

by itself? How many creatures and habitats will be affected adversely?

We

would like to know whether this is the same animal that has always been

here or if it is a new, invading species. If this is so, it gives one more

reason for protecting our seas from illegal aliens, arriving here inside

the ballast tanks of ships or otherwise. It also raises the important question

of why some animals suddenly increase their numbers so explosively, like

the crown-of-thorns starfish in the Australian Barrier Reef. Have conditions

in our seas changed? Has its natural predator disappeared? If so, who was

it? Will our local fishes learn how to eat it? Will the plague disappear

by itself? How many creatures and habitats will be affected adversely?

It was not long ago that divers reported the alien mud mussel in the Mahurangi Harbour. It also went through a period of unopposed propagation, but is now hard to find. Was it the cold water of the time that made it thrive?

By covering the sandy bottom with a dense mat, the parchment worm makes

life for traditional sand dwellers, such as clams (particularly scallops),

worms and starfish impossible. These are the losers. But our little seahorse

(Hippocampus

abdominalis) is a winner. It is rapt with the enormous expansion of

its terrain. In between the parchment tubes it finds many tiny sea slaters

and mysid shrimps, while it can hold onto the tubes with its tail,

to resist swift currents.

|

|

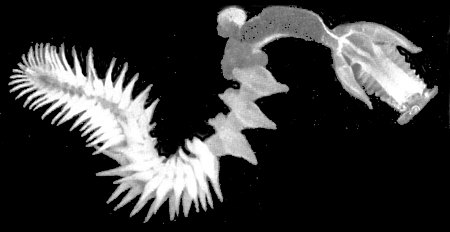

| The parchment worm belongs to the extensive family of bristleworms (polychaetes - poly=many; chaetos=fine hair). These have segmented worm-like bodies with paired legs. This rather complicated looking worm derives its scientific name from two Greek words: chaetos=bristle and pterus=wing, commonly pronounced as kee'topteres, emphasising the 'top' part, but should really be pronounced as two words: kayto-'teeroos. Its name comes from the three paired front legs that are fused into wings. By rowing these wings inside its tube, it causes a current to pass its feeding apparatus. By means of mucus, it traps minuscule plankton organisms which it eats wrapped in its own spit. |

Closeup of a parchment worm (Chaetopterus variopedatus) (From W J Dakin, 1956) |

| One always wonders how animals such as snails, shells

and tubeworms, living in rigid houses, expand their dwellings. The parchment

worm living inside its tube and being cemented to it by a bungi rope, is

not able to get outside. Besides, its tube ends in a narrow opening, too

small for the animal to pass through. So how can it make the ends grow

longer and wider?

In order to do so, it must be able to dissolve the old tube while at the same time cementing a new and larger one outside it. It may be able to do so by penetrating the (porous?) parchment with its cement glands, through growth 'cracks' much like the seams in a human skull. In this picture one can see the tapered tube openings and the worm's many droppings. |

parchment worm tubes at night. |

| The Chaetopterus parchment tubeworm feeds by fanning

water through its home tube with its wing-like legs (fan parapodia).

A bag of slime is excreted from two feeding legs (aliform notopodia).

Water flows into this bag and out through its side, trapping tiny algal

and mud particles. At its bottom end, the bag is continuously rolled up

into a ball by the food cup. Once the ball is big enough, the bag

is rolled up entirely and the compact ball of mucus transported to the

mouth over a conveyor belt of whipping hairs (ciliated dorsal groove).

Note that the parchment worm species shown in the drawing lives underground, whereas our invasive species settles on top of the sea bottom. |

|

-- Seafriends home -- indepth

index -- site map -- Revised: 20060808,20071012,